Meeting the Moment: The Value of Online Learning in a Time of Change

Graeme Cannon, Research and Foresight Associate

Did you know that the first online course in Canada was pioneered at the University of Toronto in 1986 (Bates 2016)? Distance learning—learning in a place other that the institution one attends—has been around for centuries. However, the advent and proliferation of the personal computer and internet made online distance learning a viable method of learning.

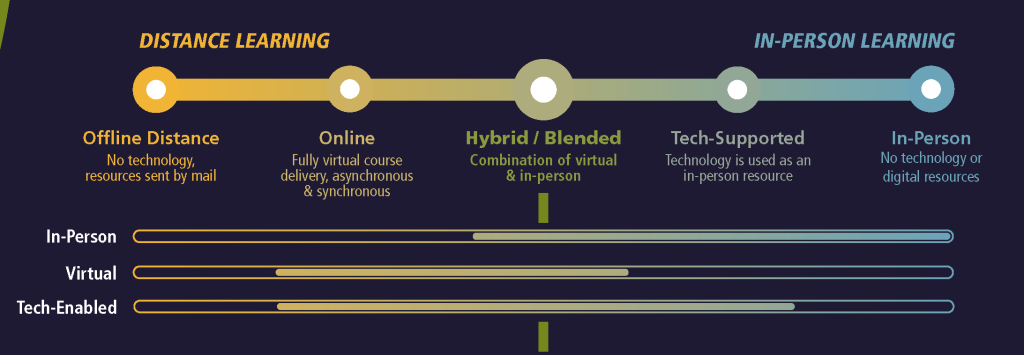

Since the 80s, technological advancements have improved the distance learning experience. At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, higher education institutions shifted to emergency remote teaching, wherein a distance education model was adopted for all classes. This form of learning continued in some form—hybrid to fully online—throughout the pandemic. Online learning continues to have value to provide to institutions—in the forms of cost-saving, net-new revenue by reaching new learners in increasingly accessible ways and promoting upskilling and reskilling for the Canadian labour force—amidst this landscape. This article will showcase the value that online learning has today, in our current moment, beyond the limitations brought about by the pandemic, for learners, instructors, and institutions alike. In this article, online learning is inclusive of both synchronous and asynchronous modalities. It refers to the entirely virtual format of course delivery.

After the pandemic, educational institutions, governments, and individual citizens have highlighted issues they have with online learning. The University of California banned fully online degree offerings (D’Agostino 2023b). Similarly, China revoked the ability for students to partake in online learning programs abroad while studying from home (D’Agostino 2023a). Harvard University has emphasized their rule that students must attend class in-person, with the Dean of Undergraduate Education stating that “an education conducted over Zoom would not be worthy of the Harvard name” (Brennan, Parker, and Robinson 2024). One author in the Globe and Mail writes that “the accidental experiment with online learning made one thing crystal clear: There is no replacement for the interactions that come with being in a classroom” (Alphonso 2024).

However, there is value in online learning. As Ontario’s postsecondary institutions grapple with financial deficits, online learning provides a potential lifeline. Online learning provides benefits for both learners and institutions. Amongst the benefits for learners are the ability to: study and attend classes from anywhere at any time, interact closely with other students and the instructor at any time, and navigate course materials online. Institutions are likewise able to expand their reach, allowing non-traditional learners or learners from diverse or remote geographic markets to attend the institution (Kasarie and Kasarie 2010; Mhlanga 2024). Before the pandemic, online learning was traditionally for those who couldn’t attend an institution easily, but now its purpose and intended audience has changed, becoming one of several modalities that institutions can offer (Lockee 2021).

This ability to reach other markets and the potentially asynchronous nature of online learning go hand-in-hand to support both learners and institutions. Online learning can reach otherwise hard to reach markets, both geographically and temporally (Kasarie and Kasarie 2010; Mhlanga 2024). Moreover, online learning also provides an avenue for offering upskilling and (re)training to working learners. In the end, online learning is cost-effective for students who are able to save on travel, accommodation, and expenses.

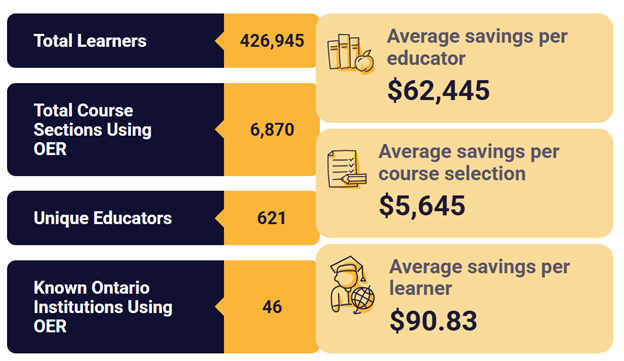

Digital Experiences

Learners view these benefits as very important, in general preferring hybrid formats (Muller and Mildenberger 2021). Learning from anywhere at any time allows learners to save time and money due to a lack of travel and rent to pay. Being able to review materials, including recorded lectures, promotes student studying at times that work better for them (Manea, Macavei, and Pribeaunu 2021). If a student misses class for any reason, online and hybrid learning environments allow them to catch up on their own time. This promotes a better work-life balance with reduced expenses, in turn allowing student’s more time to focus on their studies. By investing in online education infrastructure, the per person cost of learning decreases and the institution’s market reach expands. It provides a “cost-friendly alternative to a traditional classroom” (Kasarie and Kasarie 2010). Providing and scaling online learning does not need to be costly: an analysis of online classes shows that material that involves only-learner content—without much instructor interaction—has both the lowest cost-per-enrollment for the institution and the highest completion rate (Mishra 2025). Running courses asynchronously also supports lower costs. Because there is no reported compromise to learning outcomes, institutions should offer and promote online learning options (Müller and Mildenberger 2021). Moreover, the use of Open Education Resources (OER) supports lowering costs further. For examples of student savings, please see how eCampusOntario is tracking student savings through the uptake, adoption, and adaption of online teaching materials here: https://openlibrary.ecampusontario.ca/impact/.

Figure . eCampusOntario (2025).

There are unfounded concerns that online learning is not as successful as in-person learning. Educational outcomes from online learning improve as instructors become more familiar with the skills and technologies utilized in facilitating expanded online teaching (Tate and Waschauer 2022). According to a multitude of studies, online learning provides an equivalent or higher education quality in meeting learning outcomes (Mishra 2025; Müller and Mildenberger 2021; Zeng and Luo; Mutalib, Akim, and Jaafar 2022). Thus, the flexibility afforded by online learning can allows learners to decide how, when, and where they learn with no impact on their learning outcomes.

Digital skills, in some form, are explicitly required to participate in online learning. However, there is no correlation between having digital skills and any impacts of online learning, though they do make online learning easier (Eynon and Malmberg 2021). Lifelong learning thus may require upskilling one’s digital skills. Learners have the digital skills in technology use and familiarity with online environments, but may struggle with time management and other traditional human skills (Karatas and Arpaci 2021; Dogham et al 2022). Online learning supports students’ digital literacy and skills development.

Learner Engagement

According to Hira and Anderson (2021), learner engagement decreased during emergency remote teaching. As such, changes in assessments and engagement should be undertaken in online classes, such as self-directed or project-based learning, to help learners to develop skills such as collaboration, self-motivation, and time management (Hira and Anderson 2021). Interactivity, student leadership, and flexibility should be encouraged in online learning environments to help learners develop key workplace skills (Dogham et al 2022).

There are concerns learners be more distracted during online learning. Digital distraction may be common, which is using digital technology for non-learning purposes when one should be focused on their learning environment. There are several types, such as multitasking, mind-wandering, and unexpected interruptions. These require self-regulation to overcome (Wang 2022). Research by Mutalib, Akim, and Jaafar (2022) supports this definition, finding family, time-management, and other online distractions as things learners face online. As such, helping learners to develop self-directedness is important in online learning (Wang 2022). Learners must attain motivation and avoid distractions during their learning to complete their studies. Other ways to increase student motivation include promoting digital upskilling, providing collaborative environments, enhancing instructor knowledge and skills, supporting instructor well-being, and being aware of technological inequities that can emerge (Chiu, Lin and Lonka 2021).

Accessibility

Online learning arrangements and the flexibility provided may have facilitated greater homework completion and more asking of questions in synchronous environments by students (Mutalib, Akim and Jaafar 2022). Students who are aware of how they learn and can manage their own learning processes have great readiness for online learning. However, instructors must be able to support those who lack motivation (Karatas and Arpaci 2021), through instructor presence (Suswastini, Dewi, and Dantes 2023) or support (Riti, Mijiyati, Sukamto, and Hariri 2022).

Online learning also offers greater access for learners who require accessibility supports. Indeed, there are innovations happening in online learning environments that are creating engaging and accessible educational experiences. Students need not feel isolated or miss the hands-on aspects of in-classroom learning due to advancements in the mixed, augmented, and virtual reality spaces (Lockee 2025). There are, however, worries that OER and other materials are often English heavy and not ideal for non-English speakers (Rets, Coughlan, Stickler, and Astruc 2023). With advances in translation artificial intelligence, this worry may be less of a concern. Moreover, one recommendation for increasing accessibility is to use simple language, which OER should endeavour to do regardless (Rets, Coughlan, Stickler, and Astruc 2023). Materials of all forms can be used in online learning, and while they have different considerations , they can support learner needs (Russ and Hamidi 2021). As the number of learners with recognized disabilities increases, so too do the supports required (Guilbard, Martin, and Newton 2021). Online learning provides the flexibility to best support these learners.

All in all, there are many benefits to online learning. With digital technologies, learners can encourage themselves to learn, problem solve, and gain new skills. Self-motivation and necessary workplace skills—both digital and human skills—can be learned and improved with online learning. Online learning provides flexibility to learners—anywhere, anytime, especially in asynchronous environments—with no impact on learning outcomes. Online learning is more accessible for learners with disabilities. It is cheaper too, for students and institutions, especially after infrastructure is available and maintained. Online learning lets institutions reach new and emerging markets to support workforce training, upskilling, and reskilling. Overall, online learning offers unique benefits to learners and institutions alike. The technology is here, digital transformation is afoot, the cost of living is high, and online learning provides an entwinement that helps everyone meet this moment.

References

Alphonso, C. (2024, December 1). Why Canadian universities are facing an identity crisis. The Globe and Mail. https://globe2go.pressreader.com/article/281689735580660

Bates, T. (2016, January 17). Celebrating the 30th anniversary of the first fully online course. Online Learning and Distance Education Resources. https://www.tonybates.ca/2016/01/17/celebrating-the-30th-anniversary-of-the-first-fully-online-course/.

Brennan, M. T., Parker, A. J., and Robinson, T. R. (2024, December 4). FAS sees rise in leaves of absence as students pursue entrepreneurship and athletics. The Harvard Crimson. https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2024/12/4/fas-leaves-of-absence-entrepreneurs-athletes/

Chiu, T. K. F., Lin, T., & Lonka, K. (2021). Motivating Online Learning : The Challenges of COVID-19 and Beyond. Asia-Pacific Edu Res, 30(3), 187-190. Doi: 10.1007/s40299-021-00566-w.

D’Agostino, S. (2023, February 9). China bans students from enrolling in foreign online colleges. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2023/02/09/china-bans-students-enrolling-foreign-online-colleges

D’Agostino, Susan. (2023, February 26). University of California system bans fully online degrees. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/tech-innovation/digital-teaching-learning/2023/02/26/university-california-system-bans-fully

Dogham, R. S., Elcokany, N. M., Ghaly, A. S., Dawood, T. M. A., Aldakheel, F. M., Llaguno, M. B. B., Mohsen, D. M. (2022). Self-directed learning readiness and online learning self-efficacy among undergraduate nursing students. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences, 17.

eCampusOntario. (2021). The Learning Delivery Spectrum. The Hybrid Futures.

eCampusOntario. (2025, August 12). Statistics. eCampusOntario Open Library. https://openlibrary.ecampusontario.ca/impact/.

Eynon, R and Malmberg, L. (2021). Lifelong learning and the Internet: Who benefits most from learning online? British journal of Education Technology, 52(2), 569-583. Doi:10.1111/bjet.13041.

Guilbaud, T. C., Martin, F., & Newton, X. (2021). Faculty Perceptions on Accessibility in Online Learning: Knowledge, Practice and Professional Development. Online Learning, 25(2), 6-35. Doi: 10.24059/olj.v25i2.2233.

Hira, A., & Anderson, E. (2021). Motivating Online Learning through Project-Based Learning During the 2020 Covid-19 Pandemic. COVID-19: Education Responds to a Pandemic, 9(2), 93-110.

Karatas, K, & Arpaci, I. (2021). The Roles of Self-directed Learning, Metacognition, and 21st Century Skills Predicting the Readiness for Online Learning. Contemporary Educational Technology, 13(3). Doi: 10.30835.cedtech.10786.

Kasarie, N, & Kasarie, E. (2010). Economies Of Elearning In The 21st Century. Contemporary Issues In Education Research, 3(10), 57-62.

Lockee, B. B. (2021). Online education in the post-COVID era. Nature Electronics, 4, 5-6.

Manea, V. J., Macavei, T., & Pribeanu, C. (2021). Perceived benefits of online lectures during the pandemic: a case study in engineering education. Pro Edu International Journal of Educational Sciences, 3(4), 35-41. Doi: 10.26520/peijes.2021.4.3.35-41.

Mhlanga, D. (2024). Digital transformation of education, the limitations and prospects of introducing the fourth industrial revolution asynchronous online learning in emerging markets. Discover Education, 3(32). Doi: 10.1007/s44217-024-00115-9.

Mishra, S. (2025). Can online learning be scaled using a frugal approach? Journal of Open, Distance, and Digital Education (JODDE), 2(1), 1-13. Doi: 10.25619/qy1tsg74.

Müller, C., & Mildenberger, T. (2021). Facilitating flexible learning by replacing classroom time with an online learning environment: A systematic review of blended learning in higher education. Educational Research Review, 34.

Mutalib, A. A. A., Akim, A. M., & Jaafar, M. H. (2022). A systematic review of health sciences students’ online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Medical Education, 22. Doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03579-1.

Rets, I, Coughlan, T., Stickler, U., & Astruc, L. (2023). Accessibility of Open Education Resources: how well are they suited for English learners? Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance, and e-Learning, 38(1), 38-57. Doi:10.1080/02680513.2020.1769585.

Riti, R., Mujiyati, Sukamto, I, & Hariri, H. (2022). The Effect of Self-Directed Learning on Students’ Digital Literacy Levels in Online Learning. International Journal of Instruction, 15(3), 329-344. Doi: 10.29333/iji.2022.15318a.

Russ, S. & Hamidi, F. (2021). Online Learning Accessibility during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Proceedings of the 18th International Web for All Conference (W4A’21).

Suwastini, N. K. A., Dewi, K.I.R, & Dantes, G. R. (2023). Benefits of online learning according to recent studies. Jurnal Invasi Teknologu Pembelajaran, 10(1), 32-42. Doi: 10.17977/um031v10i12023p32.

Tate, T, & Waschauer, M. (2022). Equity in online learning. Educational Psychologist, 58(3), 192-206. Doi: 10.1080//00461520.2022.2062597.

Wang, C. (2022). Comprehensively Summarizing What Distracts Students from Online Learning: A Literature Review. Human Behaviour and Emerging Technologies, 1-15. Doi: 10.115/2022/1483531.

Zeng, H & Luo, J. (April 2023). Effectiveness of synchronous and asynchronous online learning: a meta-analysis. Interactive Learning Environments, 32(8), 4297-4313. Doi: 10.1080/1049820.2023.2197953.